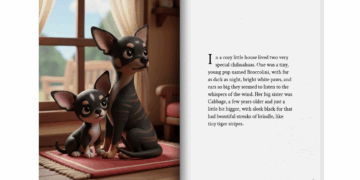

Remnants of a camp near a bridge in midtown Santa Fe (Kaveh Mowahed/KUNM)

In traffic on St. Francis the other day, we passed a person panhandling on the median and my

daughter asked, “Don’t you feel so guilty?” I said, “yes” and also, “I so rarely carry cash”— a kind of

excuse that, as I said it, felt insulting and weak — especially given the values I’ve raised both my kids

with. My oldest, for example, gives cash frequently and once ran into REI to buy gloves for a man

shivering on a bench during a particularly cold winter day.

As I drove, I wondered how anyone panhandling makes it now because I know I’m not alone in

infrequently carrying cash. I thought about how hardened I became when I lived in India, how at

first I gave all my money away and then learned to shut off the part of me that felt empathy and

responsibility because there was no actual way I would ever have enough money to give to everyone

on the street. That hardness scared me then but it scares me more now because it gives me raw,

personal insight into our capacity to diminish another person’s humanity and suffering. It is easier to

turn away from another person than it is to truly see them. It is easier to look past a person sleeping on

the street than to begin to acknowledge the systems in which we are embedded that makes it possible for

some people to have multiple homes and some to have no homes at all. It is easier to make the kind

of pitiful excuse I made to my daughter than to stop at an ATM and get some cash.

In light of the ramping up of the federal government’s dehumanization of broad categories of

people, from immigrants, trans people, people with autism, Palestinians and other people calling for an end to

genocide in Gaza — to name just a few groups — it is clear that denying someone’s humanity is a way

of deflecting shame and the feeling of powerlessness. I feel powerless when I see someone

panhandling because whether or not I have cash or a sandwich to offer, I don’t know what to do to

make a world where everyone has access to housing and healthcare and where no one is seen as

disposable.

I don’t even know where to begin with countering stereotypes that serve as a kind of justification for

disposing of people; myths about who was homeless and why that were propagated when Reagan

came into office in 1981 and gutted federal funding of housing development — along with many

other poverty alleviation safety net programs. These stereotypes rooted so deeply into our society

that it hardly matters what side of the political spectrum you fall on — I have heard rabidly anti-

homelessness rhetoric from self-described “liberals” as much as I have from people on the right.

I can’t help wondering what would happen if we all sat with the discomfort of homelessness. While

conversations about people living on the streets most often center on stereotypes or discussions of

“safety” (it’s worth noting that our safety is being threatened much more by those in power right

now), sometimes it becomes clear that there are many people who think homelessness is what a

person deserves. This perspective is an eerie reflection of current conversations about ICE

abductions and due process — there are an alarming number of people in our country who seem

comfortable with the idea that some humans don’t deserve due process, or housing or food. I can’t

help wondering if this perspective is, at its root, based in fear: What if I am not deserving of a freedom or a

home?

So much of my life and anyone’s life is about chance — the randomness of being born in a particular

time and place. The randomness of having a family that supports me — and the randomness of being

alive right now to face the violent collapse of empire. This is as intimate and personal as it is global.

Even if we can’t individually fix giant systems designed to pit us against each other, we can practice

empathy and humanity toward each other. We’re in this together.

This post was originally authored and published by Emily Withnall from via RSS Feed. to get your news feed on Nationwide Report®.