Excerpted from “Here Beside the Rising Tide: Jerry Garcia, the Grateful Dead, and an American Awakening” by Jim Newton. Copyright © 2025. Available from Penguin Random House.

It is frequently the case that cultural and political movements emerge, thrive for a while and then produce backlash.

Jim Crow can be seen as a response to the end of slavery, and civil rights to Jim Crow; the Moral Majority to Roe v. Wade; Donald Trump and “Make America Great Again” to Barack Obama and “Yes, We Can.” Sometimes the backlash is long in coming, while other times it arrives quickly. In the case of the American 1960s, the backlash came even before the movement understood itself, even before it knew what it was.

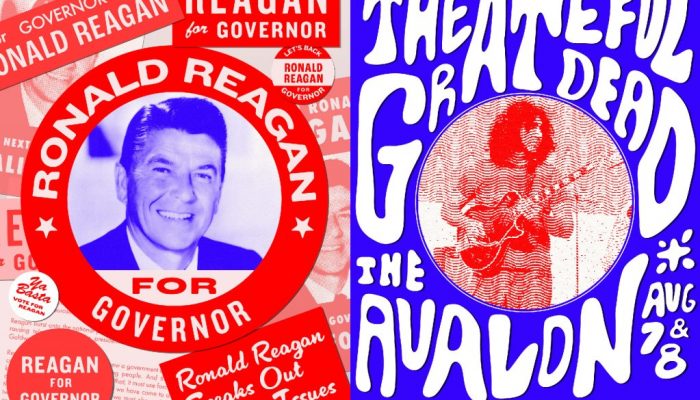

Over the course of one year, 1966, a new notion began to take shape and an old idea rose up to push the new back down — or at least to try.

The Acid Tests and their offspring were the new. They represented a suite of ideas — experimentation and improvisation; culture wrapped around politics; communalism and joy; drugs, sex, music, love; restless values in rebellion — against what, they did not quite yet know. The backlash came from discomfited adults, and it gravitated to the candidacy of one man in particular: Ronald Reagan. As the Acid Tests darted across California in 1966, Reagan ran for governor. The two campaigns, one improvised, the other studiously deliberate, circled each other, competing for adherents.

As the year opened, the Grateful Dead were returning to San Francisco. Reagan, after months of traveling the state, officially entered its politics. “Ronald Reagan and A Need for Action!” the opening banner announced in the film released first to the California press on Jan. 3 and then to the public on Jan. 4. It included an exclamation point, but the presentation that followed was deliberately muted, a stern appeal from a reassuring man. Reagan was concerned about the condition of California, which had been reliably Republican, only to have riots and hippies put that history to the test. Now, Reagan was also here to make the case for old values, to make things right again.

Old California was pioneers and visionaries, panners for gold, makers of movies. New California was rioters in Watts, spoiled kids at Berkeley, and drug parties featuring the Dead.

Reagan was the picture of conservative values. He strolled around his polished living room, complete with leather chairs and brass lamps, a grandfather clock next to a fireplace where a fire burned. Speaking directly into the camera, Reagan was poised and forceful but hardly alarmist. Yes, he was announcing his intention to depose California’s incumbent governor, the garrulous and personable Pat Brown, but Reagan never mentioned Brown by name. His criticisms of “the executive branch” were severe but never mean.

When it came to discussing the children of the state, Reagan’s demeanor noticeably hardened. It had taken effort and money, Reagan noted, for California to build a “great university,” but that was not enough.

“It takes more than dollars and stately buildings,” he said, one hand on one of those leather chairs, the other in his pocket. “Or do we no longer think it necessary to teach self-respect, self-discipline, and respect for law and order? Will we allow a great university to be brought to its knees by a noisy, dissident minority? Will we meet their neurotic vulgarities with vacillation and weakness, or will we tell those entrusted with administering the university we expect them to enforce a code based on decency, common sense, and dedication to the high and noble purpose of that university; that they will have the full support of all of us as long as they do this, but we’ll settle for nothing less?”

For Reagan, this was an appealing political situation. The reports from Berkeley were, at least to those of Reagan’s generation and sensibilities, alarming. Radicals had somehow gained a foothold, outwitting their elders in an argument over what constituted learning, contesting even such notions as freedom and citizenship. Reagan’s central argument was that California was being mismanaged by soft leaders. Parents wondered about the taxes they paid to send their students off to the nation’s greatest public university system, only to have that system become a cradle of incivility and rebellion. Reagan understood. He pounded the university, knowing that it was the pride of his opponent.

Reagan entered the contest with other political winds at his back, notably in California’s frayed race relations and growing white discontent with Black demands for justice. The Watts riots back in 1965, still smoldering in California politics, were the other pillar of that case.

Those riots had begun shortly after 7 p.m. on August 11, 1965, when two California Highway Patrol officers pulled over Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old Black man suspected of drunk driving in Watts, a neighborhood south of downtown Los Angeles. The officers pulled Frye’s car to a stop not far from his house. As they put Frye through sobriety tests, his mother and brother saw what was happening and defended him, loudly arguing with the officers. A crowd began to gather, and when the CHP took Ronald and Rena Frye into custody, the situation devolved. Within hours, a thousand people were in the streets, wrangling with police through the night.

That was just the beginning, a “prelude to Act I of a terrible tragedy,” as the Los Angeles Times put it. Over the next two days, 34 people died as violence spread outward from Watts and throughout south L.A. Racism, redlining, police brutality, the grinding effects of poverty, all simmered beneath the surface of the riots, but polls afterward showed that white Americans overwhelmingly believed “that the riots were started and carried out by irresponsible Negroes.” Those sentiments — resentment that Black people did not appreciate California’s efforts at desegregation, anger that Black people would resort to violence — suggested a core of white discontent.

Black activists would find common ground with the nascent counterculture. Whites, bewildered and self-righteous, would find their way to Reagan.

As Reagan well knew, Brown was vulnerable on both the events at Berkeley and the riots. The university was Brown’s most beloved contribution to California, and he was conspicuously absent for Watts, vacationing in Greece when the riots broke out, so every reminder of the riots was a new reiteration of the charge that he was missing when it mattered. And that was, after all, Reagan’s larger, only vaguely subtextual point: that adults had fled the scene, that teenagers — or Black people — were running wild.

Proof of that were the Acid Tests. The sight of young people, high on God knows what, dressed in weird clothes, their hair long and unwashed, resurfaced old images of “Reefer Madness” and disreputable Beatniks; it was enough to unsettle the most complacent parent. They seemed of a piece with protest and riots — part of the mounting sense that something was slipping away, some shared commitment to order, to American values. Something new was afoot, and to them it did not seem good. It felt to some like communism, not because most Americans knew much about communism but because, like communism, this new force, this growing energy, was threatening, subversive. People — voters — were afraid.

Reagan reminded them that they hadn’t always felt this fear, that they had a right to security. These were their children in these schools. How could they sit still as their own children rejected their values? It was so obviously wrong, and surely it could not be their fault. They worked hard, paid to build the colleges that now threw their intellectual superiority back in their faces, paid for the social programs meant to show that they cared about Black people, who now rioted in response. How dare they?

Reagan assured them that it was not their fault, that others — drug dealers, well-intentioned but misguided leaders, yes, even communists — were behind this unrest, and that he would tend to it.

“In 1966, the world, and especially California, was changing fast. The change was actually visible on the streets of San Francisco, at places like the Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom.”

ROBERT STONE, NOVELIST AND MEMBER OF THE MERRY PRANKSTERS

As Reagan stalked Pat Brown, Jerry Garcia responded with what looked like indifference. Reagan denounced drugs and young misfits; Garcia and the Dead dropped acid and performed, every bit the misfits that Reagan made them out to be. Through the winter and spring of 1966, they moved up and down the coast, crisscrossing Reagan’s campaign and ignoring the candidate’s challenge to everything they stood for.

The Dead, as has often been noted, were not political, at least not in the sense in which we are accustomed to considering politics. They did not endorse Pat Brown or appear at benefits for him. They did not raise money for candidates or try to turn out young voters.

But that defines politics too narrowly. These were inherently political days. Culture and politics swirled together. Getting high was political. Dancing was political. An Acid Test was an evening of fun and experimentation but, importantly, also an act of defiance. If one considers politics broadly — as protest, as the clash of values and ways of living — the Dead were at the center of California politics in 1966.

“In 1966, the world, and especially California, was changing fast,” Robert Stone, a friend of the Merry Pranksters, wrote. “The change was actually visible on the streets of San Francisco, at places like the Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom. Political and social institutions were so lacking in humor and self-confidence that they crumbled at a wisecrack.”

What was the Trips Festival but a wisecrack?

This post was originally authored and published by Jim Newton from Cal Matters via RSS Feed. Join today to get your news feed on Nationwide Report®.