In the coming years, Texas is set to receive billions of dollars to address the ongoing opioid crisis that has taken the lives of more than 10,000 Texans between 2020 and 2023, per state data. Already, the state has allocated over $100 million in funds to cities and counties. Some local governments have begun to use the money, while others haven’t spent a dime.

The payouts come from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors, and consultants for their role in pushing prescription opioids across the country. The funds, which will be distributed annually for the next 18 years, are coming as recent cuts under the Trump administration hit both Medicaid and the federal agency serving people with substance use disorder. Meanwhile, the spread of more potent opioids, including fentanyl, has been met with an increasingly militarized border crackdown that experts say doesn’t address the root problems.

The last time corporations paid out legal settlements for harming public health—the big tobacco settlements from more than two decades ago—much of the money was not used to curb smoking or the harms associated with it. This time around, experts say that how the opioid funds are used in these early years could set the tone for the next nearly two decades that Texas receives settlement dollars.

“We have this opportunity here to actually get money into areas that have been afflicted,” said Tyler Varisco, director of the Pharmacy Addictions Research & Medicine Program at the University of Texas at Austin. “There is a tremendous amount of public benefit in ensuring that these funds are spent responsibly.”

That’s why researchers, advocates, and the press are keeping a close eye on how that money is spent. In Texas, the Opioid Abatement Fund Council—led by 14 state appointees—is in charge of awarding most of the money through grants to nonprofits, universities, hospitals, and local governments, depending on the specific grant requirements. Meanwhile, 15 percent goes to state agencies and another 15 percent to counties and municipalities, which aren’t required to disclose their spending.

To fill the local transparency gap, Katie Harris of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy reviewed budgets and records from 21 jurisdictions, categorizing about $60 million in settlement funds. Her findings, released in August, show millions already spent on services for prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm reduction, aligning with nationally recognized principles on use of opioid settlement funds.

Collin County is using some of the money to hire recovery coaches. Bexar County is supporting sober housing. Dallas and Travis counties are funding peer-support programs. Many places are expanding medication assisted treatment, in which patients are prescribed less potent opioids such as methadone or buprenorphine to reduce cravings and prevent withdrawals.

There were also several purchases of naloxone, an overdose-reversing nasal spray commonly known by its brand name Narcan. It’s available over the counter for about $30 to $50 for a pair of doses, freely available through various harm-reduction groups, and kept in some schools and by some first responders.

Others are focusing on law enforcement. In Montgomery County, funds are being used on phone forensic tools to identify drug dealers. Plano’s police department is investing in drug-testing kits, protective gloves, and training. Tarrant County and the City of Dallas are putting money into drug court systems.

“If we don’t invest in evidence-based services to address this crisis, we’re just going to see this problem continue and potentially increase,” said Magdalena Cerdá, director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at New York University. She pointed to fentanyl and xylazine test strips as an additional tool for harm reduction, but they are outlawed in Texas despite recent efforts to legalize them.

Other cities and counties, meanwhile, are diverting or not using the money.

Nueces County, which has seen 134 opioid-related deaths since 2020, put its settlement funds into its general fund to avoid having to raise taxes, according to Harris’ findings. Harris County, which had the highest number of opioid-related deaths in the state every year since 2020, has yet to spend or earmark any of the $6 million it received, though the City of Houston has begun to use its portion. Corpus Christi didn’t disclose how funds were being used.

In addition, according to the Texas Observer’s review of state Comptroller data, about $250,000 of the allocated funds so far, less than 1 percent of the total, has yet to be claimed by dozens of cities and counties in any of three yearly disbursements since 2023. If funds aren’t claimed within two years, the funds will be redirected to the state opioid abatement council.

Baylor County, population 3,500, in North Texas has about $20,000 in unclaimed funds. The county treasurer, Kevin Hostas, told the Observer that the county commissioners chose not to accept the funds, but Hostas was unaware as to why. In Shenandoah, a small town next to The Woodlands, $31,000 has been unclaimed; the city’s administrator thinks the funds could have better use elsewhere since they have no programs and no opioid crisis.

“Shenandoah is a small city with a geographic footprint of 2.2 square miles. We are not experiencing an opioid problem at this time, nor do we have programs or city facilities that deal with this issue. There’s nothing to apply those funds to in Shenandoah, which is why we have not claimed them. It would be great if those funds could be redistributed to areas that badly need them,” Kathie Reyer, the city administrator for Shenandoah, said in a statement.

Researchers say small allocations do make it hard for rural or sparsely populated areas to launch programs on their own, while they note that funding could be given to regional organizations or neighboring localities. But Marcia Ory, professor at the Texas A&M University School of Public Health and co-chair of the university’s Health Opioid Task Force, warns against municipalities that may not have many or any opioid-related deaths being complacent.

“You don’t know you have a problem till you have a problem,” she said, pointing to recent fentanyl-linked overdoses in Cleveland ISD in East Texas. Ory received a grant from the state council, funded by settlement dollars, that will help her team conduct community events in schools across the state to address youth prevention. She thinks smaller prevention events could be replicated by other local governments. “The bottom line is it doesn’t have to be a huge amount of money to make a difference.”

Events like these are already happening across the state, particularly in late August around International Overdose Awareness Day. In Amarillo, an organization founded by a mom who lost her son to an overdose hosted an event with inflatables, live music, food trucks, and free Narcan. And in Montgomery County, a similar event took place that originated years ago when four moms who lost their sons to opioids met in a grief recovery group.

“We decided that instead of meeting people after their loved ones passed away, after the grief, that we could go out and do something to make a difference in the community,” Kimberly Rosinski, one of the founders of the nonprofit Montgomery County Overdose Prevention Endeavor (M-COPE), told the Observer at the event.

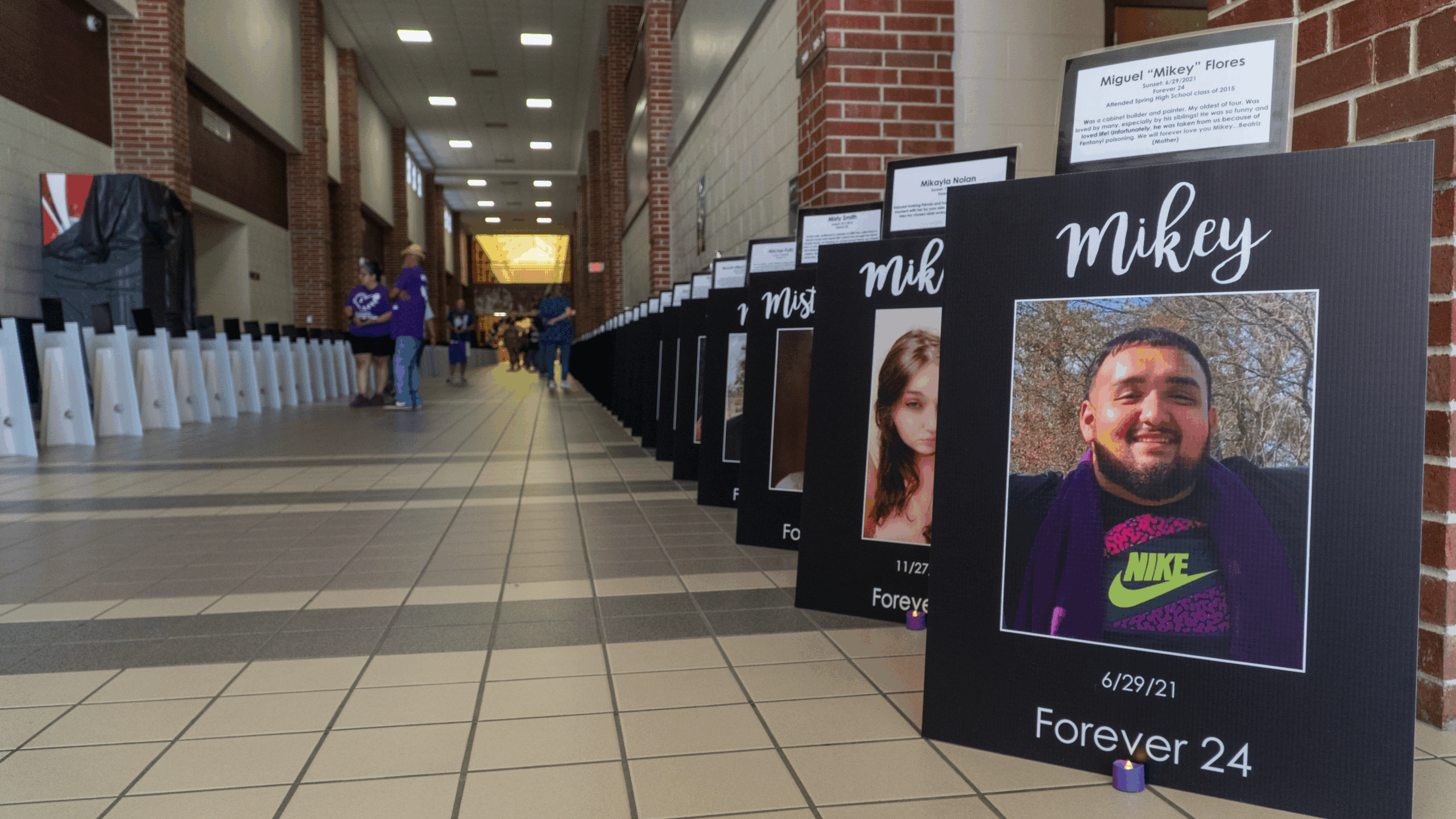

Now in its fifth year, the event hosted dozens of local organizations and a former NFL football player, Jason Phillips, who recounted his story of addiction. Thousands of dollars were given out in scholarships. The school’s hallways displayed hundreds of portraits of people across Texas who have died after a substance overdose.

At the center of the school, a balloon display split into three colors allowed people to share how their loved ones are affected by substance use disorder: white for sobriety, black for loss, and red for active use.

“It’s been very healing for me to not just stay in that grief but to try and do something positive with that,” Rosinski said, wearing a jersey with her son Stephen’s name and his football number, 50.

While these events are happening in a handful of cities and counties, researchers like UT-Austin’s Varisco said that there should be a place for these ideas and outcomes to be shared among local officials across the state.

“I would want to have opportunities for people to learn from each other to ensure that we’re not buying things that aren’t going to work or spending where it doesn’t matter,” he said. “And that’s what I’m most worried about right now is that we do have this opportunity to make some real differences and some real changes and then that we’re just not going to fully capitalize on that because there is no guidance and there is no expertise to go along with these areas.”

The post How Texas Localities Have (and Haven’t) Spent Settlement Funds to Fight the Opioid Crisis appeared first on The Texas Observer.

This post was originally authored and published by José Luis Martínez from the , a nonprofit investigative news outlet and magazine. Sign up for their , or follow them on and .